Mental illness comes from bad parenting and makes you violent! But it will be cured if an expert uncovers the childhood trauma from which it stems! These are just a few of the mental health myths that have been, and continue to be circulated in entertainment films and other media.

Our project Demons of the Mind (named after a 1972 Hammer Horror film) explores how cinema has engaged with and influenced public and professional understanding of mental health during the long-Sixties period, spanning the late-1950s to mid-1970s. This was the period when psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts – collectively referred to as the ‘psy’ professionals – were in deep conflict over developments in theories and clinical practices, such as the psychiatric use of antipsychotic and psychotropic drugs, the influence of personality and genetics on behaviour, children’s emotional development, obedience and bystander apathy, psychology’s role in defining sexuality, gender, and women’s oppression, the popularisation of psychotherapy, and emergence of the anti-psychiatry movement.

It was also a period in which cinema became increasingly preoccupied with psychological ideas and films from genres such as horror, science fiction, crime and psychological thrillers constituted key ways in which new theories and research findings were disseminated and debated within the public sphere. Hollywood and British cinema invested heavily both financially and creatively in exploring disturbances of child development, attachment and mothering, psychogenetics, psychopathy and personailty disorders within overlapping cycles of genre films featuring their most celebrated directors and stars.

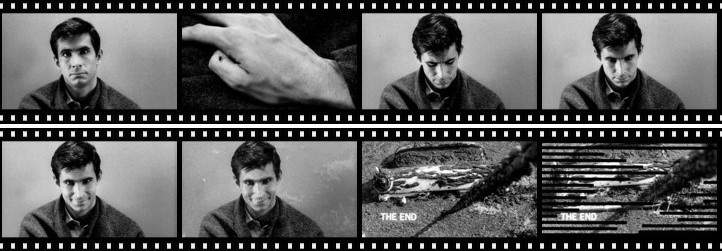

Is Norman’s mother to blame?

For example, in 1960 Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho established the trope of the pitiable psychopath – the product of parental over-attachment or abandonment, or both – exemplified by the lead character Norman Bates. The film not only established representational conventions of the serial killer and slasher film genres, but also contributed to wider media discourse and public debates about the origin and dangers of mental illness, including the promulgation of ‘psycho’ as a common and invariably pejorative label.

But Psycho is just one of many films that were produced and circulated during the period (check out some of the other films we are studying in our timeline), which engage with issues of mental health in diverse and often contradictory ways. Psycho is itself a complex cultural and historical entity that raises as many questions about causes and conceptions of mental illness as it answers. Is Norman the dysfunctional creation of a tyrannical Mother, or is Mother an elaborate fantasy created by a calculating and murderous Norman? This is an issue that has divided critics since the film was first released.

In the penultimate scene, a psychiatrist is introduced as a character to offer an explanatory case history (a standard Hollywood trope at the time). Woven into the story as it unfolds on-screen, the psychiatrist explains that Norman’s psychosis stems from the over-involvement of his mother – referred to as ‘a clinging, demanding woman’– following his father’s death, and Norman’s resultant jealousy when, after many years, she detaches from him and takes up a lover: the trigger for his murder of both mother and lover.

But, as the psychiatrist explains, he obtained the whole story not from Norman, but the Mother, or, more precisely, ‘the Mother-part of Norman’. Is this a reliable narrator? The domineering and prudish Mother of Psycho is a personality fabricated by Norman – a projection, perhaps, of his own disgust, shame, and guilt, rather than the introjection of the real Mrs Bates’ voice? –does not necessarily correspond with other clues regarding her parenting history. Maybe she was a caring or, to quote paediatrician and psycholoanalyst Donald Winnicot, ‘good-enough mother’. Film scholar Thomas Bauso goes further in claiming the ‘murdered, buried, resurrected, stuffed, carried about the house, and spoken for’ Mrs Bates as the ‘archetypal unacknowledged victim of American cinema’ (1994, 13).

The final scene serves to underscore the unreliability of the testimony of the ‘Mother-part of Norman’, as her/his inner monologue assuring us that ‘she wouldn’t even harm a fly’ is undercut by a dissolve to his/her victim’s car – owned by lead character Marion Crane with her brutalised body in the boot – being pulled from the swamp.

How, exactly, did the film director, screenwriters, and actor decide what to include (and leave out) in their cinematic portrayal of psychotic behaviour and thought processes? In what sense is Norman’s psychology revealed or re-enacted for audiences? And what does the portrayal of madness in Psycho tell us about theories and related debates in the psy sciences at the time the film was released? These are just a few examples of questions and issues we will explore in the Demons of Mind research project.

What next?

We will be screening Psycho and discussing its narrative complexities and influence on mental health narratives with neuroscientist Dr Sarah Garfinkel and broadcaster Adam Rutherford at The British Science Festival in Brighton in September (book here for free). This will be the first public event we are delivering with our project partners the British Science Association (BSA), who are helping us to foster a productive dialogue between humanities and science scholars, mental health professionals, and media experts.

We will be developing and delivering a number of screenings and festival events with the BSA over the next two years, so keep an eye on our events section and Twitter feed. In the meantime, check out our research themes and interactive timeline to see what other films and issues we are exploring.

We hope you enjoy our research project website and feel free to contact us to discuss any films or draw attention to issues you think we should be looking at.