Last Friday (13th October) the High Court decided that serial killer Ian Brady’s body must be disposed of with ‘no music and no ceremony’. Chancellor of the High Court Sir Geoffrey Vos declined Brady’s wishes to play a rendition of Songe d’une Nuit du Sabbat (Dream of the Night of the Sabbath), the fifth movement of the Symphony Fantastique, at his cremation, stating that the Gothic ‘theme and subject of the piece means legitimate offence would be caused to the families of the deceased’s victims.’

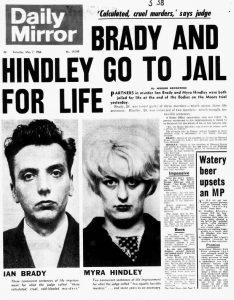

This debate over whether giving voice to Brady’s psychology is the same as empathising with him, stretches back over fifty years, and prompted Parliament to threaten to deport one of New Hollywood’s most promising film directors. Five years before he shocked audiences with a possessed teenage girl masturbating with a crucifix in The Exorcist (1973), William Friedkin outraged the British press, public and politicians by revealing he was making a film exploring Brady and Myra Hindley’s psychologies. The general consensus was that such a project was unethical, even unrepresentable.

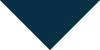

Out of the 1966 Moors murder trial emerged a key critical debate in British media and literary circles: was it ethical, or even possible, to try to understand the motivations and psychologies of killers like Ian Brady and Myra Hindley? Pamela Hansford Johnson, author of On Iniquity: Some Personal Reflections Arising Out of the Moors Murder Trail (1967), detailed her courtroom encounters with Brady and Hindley and the professional and ethical questions they raised. Momentarily caught in Hindley’s ‘hypnotic’ gaze, she recounts: ‘I am not at all given to Gothic romanticism; yet those few moments, when I am praying that she will be the first to look away, fill me with terror’. She concluded, ‘empathy in this case is impossible. One cannot imagine oneself into the situation of Hindley and Brady, far less into their heads.’

It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that in 1968 Hansford Johnson should join politicians, the press, the public, clergy, even Hindley herself in condemning the ‘hideous and indecent proposal’ of American director Friedkin making a film about the Moors murderers. The film was to be shot on location in Northern England and in colour but, quoting Friedkin, ‘totally desaturated to remove from it any unsuitable element of gloss’. A draft script was written by Emlyn Williams based upon his non-fiction novel Beyond Belief (1967) and some initial casting decisions were made. According to his own blog, film and television actor Ray Brooks was approached by Friedkin to play Brady, following his recent critical success in Cathy Come Home (1966).

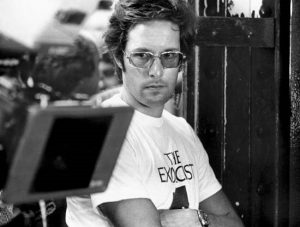

But the film was soon halted by political pressure and the intervention of cultural intermediaries. Labour MP Robert Sheldon raised the plans for the film in Parliament and called for the Secretary of State to revoke Friedkin’s visa and throw him out of the country. The Secretary of the British Board of Film Certification (BBFC), John Trevelyan, made it clear that Friedkin would never receive a certification, despite the fact that the Board was in the process of revising its policies on films recreating real murder cases. In the late-1960s, following consultation with the Independent Television Authority (ITA), the BBFC dropped its longstanding fifty and then thirty year rule of distance from crimes before being represented onscreen. This loosening of regulations in both US and UK censorship contexts allowed films such as The Boston Strangler (1968) and 10 Rillington Place (1971) to be produced and certified. But, as Trevelyan explained in his 1973 biography What the Censor Saw, the Moors murderers and their crimes were a uniquely morbid case that were beyond representation.

These conjoined press, censor and political backlashes, and threats of legal action from the families of the victims and, it is claimed, Hindley herself, derailed the film with production company Palomar Pictures backing out due to ‘the obvious difficulties, both legal and moral in presenting such a film.’ Friedkin had tried to pre-empt some of the moral concerns by insisting that the film would be based upon the factual accounts in Williams’ best-selling and, mostly, well received true crime book. But his non-fiction novel raised as many issues is it addressed because much of the book is recounted from Hindley’s perspective via passages from her controversially acquired personal diary.

Williams’ book is interesting in that, whilst it suggests Brady was on an unavoidable path since childhood, he suggest that Hindley might have evaded her fate if she had not been drawn into Brady’s spell. In the time from writing to publishing the book, the Moors murder trial – and particularly Hindley’s cold indifference in the dock – instilled a growing media and public perception that she was actually as sadistic, as monstrous, as culpable as Brady.

It took the time span of two generations of distance from the crimes for the Moors murders to be represented on screen, though in the end on television where the medium’s civic and sociological functions serve to legitimise its mediation. A main objection against Friedkin’s film was that it was intended for the commercial, entertainment medium of cinema, a concern the director tried to address by assuring that the film was also intended for television broadcast following a short theatrical run. Despite the divergence in production contexts and mediums, the BAFTA winning 2006 television miniseries See No Evil offers some insight into what Friedkin’s ‘desaturated’ film might have looked like, and how he might have dealt with Brady and Hindley’s psychology. At the same time this Granada Television dramatisation – told from the perspective of Hindley’s sister, Maureen Smith, and her husband David – confirms the impossibility of making a film based on the perspectives and experiences of Brady and Hindley in 1968.

Could Friedkin or another director return to this long-abandoned film project, or are the Moors murderers’ psychologies still beyond cinematic representation?

Fascinating read. Sort of charming to think about this sanctioned waiting period before the representation of such crimes on film. These days it feels like the movies (or at least TV movies) are being written before the trials have even wrapped up. Also interesting that these crimes and trials seem to be used mostly (in the US at least) to contextualize how they represented the broader cultural moment in which they took place (I’m thinking of the OJ series, the Menendez murders etc).